We are not what they say we are – We are what WE say we are by Christian Bell

On the 14th and 15th of July 2020, I will be joining a panel of local and international speakers who are part of a growing collective of working-class writers, thinkers, artists and researchers. All of them coming together to share, learn, empower and celebrate the contribution of working-class academics and creatives. The Working Class Academics: A Conference 2020, which will be hosted throughout virtual Zoom spaces of Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, aims to shine a light on the brilliance of working-class academia.

I have been reflecting on what the conference means to me as a working-class artist in Blackburn; a left behind labour town hit heavily by austerity measures, and hit just as hard by inaccurate and damaging media imposition. The forthcoming conference is not for those to reflect on the hardships, prejudice and in-equalities that are tied into the lives of the working class. Rather it will be a facilitation of working-class people, sharing and discussing what we DO. To talk about the value and brilliance of what we do, through a diversity of experience and background. A rectification of how we are portrayed by the media.

The media paint a sombre picture of the working class.

There is a vile and destructive scrutiny and imposition of working-class people and places portrayed to us by the media. Grotesquely formulated examinations and representations of people and place, characterizing working class misfortunes as individual behaviours and failures. We have seen implementations of this on the BBC Panorama documentaries, ‘White Fright: Divided Britain’ (2018), and ‘Trouble on the Estate’ (2012). As well as channels 5’s ‘Benefits Britain’ documentary series and channel 4’s ‘Benefits Street’; both of which generate the concept of “benefits culture”, resulting in a division between taxpayers and benefit recipients.

These propagandic national media outputs portray working class people as problematic within society. This is supported by an un-progressive and right-wing narrative which tells us from an early age that with the right amount of hard work and self-discipline, we will “get somewhere in life”. That as individuals we are wholly responsible for all our failings and misfortunes. If we succeed, we have worked hard, if we fail then we have not worked hard enough. This is a de-humanising narrative which ignores broader social contexts and dismisses left behind people as biproduct of left behind places.

Media organisations, on several occasions have targeted Blackburn where I have just finished a BA hons degree in Fine Art. Following such insidious explorations of working-class communities, the media then relay through the television screens of the general public, that people who belong to working class areas of places like Blackburn, are un-educated, un-cultured, un-engaged, and divided. The misrepresentations of these people, especially those who are in receipt of out of work benefits, are often portrayed as exploitative of the taxpayer. This spreads a general loathing for the poor who are deemed as a burden on the state. These distorted accounts also come with a risk of internalised oppression. A self-destructive acceptance of what the media are saying we are.

But we are not what they say we are.

The working-class academics conference speakers come together over a common desire of resistance and validation. Artists and creatives in Blackburn have already been responding to the media’s vulgar depiction of their people and places. The Kick Down the Barriers programme led by Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery responds directly to the Panorama documentary ‘Divided Britain’, by using engaged art practices alongside written enquiry and collaborative research methods to challenge the stigmas of segregation which tarnish their town. British Textile Biennial artist in residence Jamie Holman also challenged the media narratives of Blackburn through a body of work and exhibition Transform and Escape the Dogs during the BTB 2019. In 2019, Holman was also co-commissioned by the Kick Down the Barriers programme to work with artist Sana Maulvi. The two began writing letters to one another which explore the roots of their friendship and shared experiences of the town where their studio is located. The letters respond to the ‘Divided Britain’ narrative revealing uncomfortable moments as well as an insight into a close friendship. The letters were intended to be delivered as a performance in Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery. As a consequence of COVID-19, the artists now intend to read the letters to one another as an online performance on July 16th. A recorded video of the performance will be shown in Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery at an exhibition for Kick Down the Barriers launching on the 30th September. The recording along with their body of letters form a collaborative piece of work concluded by a simple gesture… “Fuck you Panorama.”

For details of live letter reading performance by Sana Maulvi and Jamie Holman please click here: https://www.facebook.com/events/321122942234806

We are what we say we are.

The up-coming conference will facilitate a platform for working class academics and creatives to confirm that we are not what they say we are – We are what WE say we are. The title of the conference working class academics is already a misfit within the established system. A misfit which alone resists and challenges the impositions of the media and the more established elite narratives. Just like the term working class academic, the term working class artist may also sound like an oxymoron, especially in the area of Blackburn, which has been labelled as a place with “the lowest arts engagement in the country.” And if we were not already slandered enough. We are now, as artists described as “non-essential”.

The media paint a sombre picture of the artist.

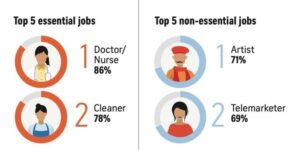

Although published in Singapore, within the Sunday Times edition of The Straits Times, a Singapore newspaper; a chart which suggests that an ‘Artist’ ranks #1 in a list of the Top 5 Non-Essential Jobs, has been circulating globally over social media. The article has rightly caused an upset among those within the creative industry.

A participant of the survey explained that the publication was only relevant to Singapore. That the newspaper asked 1,000 Singapore respondents which jobs are the most crucial for the economy and welfare of their own country during the current Covid context. Regardless to who this article was intended to be relevant, surely this is simply an example of reckless, harmful, and dis-tasteful journalism.

With a global outreach, the article sends a message which dismisses the role of the creative industries during a pandemic. Key Workers such as NHS workers, carers, retail workers and more, have all played an essential and highly commendable role within our communities during the pandemic; and most of these are recognised within the Straits Times top 5 essential list. However, it is unjust to claim that artists and those within the creative industry do not play an extremely valuable role within our communities. To label them as “Non-essential”, has triggered a feeling of de-moralisation among many within the creative industry.

The decision to include a “top non-essential jobs” list within the article was surely only ever going to cause upset and offense. And whether the list was only relevant to Singapore or not, becomes irrelevant once images of the chart start to circulate on social media. Two days after the release of the article, a friend/peer who I studied with on the Blackburn Fine Art course, after seeing the article shared with her peers: “Thinking of changing my profession… after three years of hard work. My non-essentialness makes me feel superfluous and inconsequential.” My friend was saddened and discouraged by the article. And rightly so. I have read many similar reactions to this article from artists and emerging artists across the UK, thus the outset of internalised oppression.

But we are not what they say we are.

The “non-essential” creative industry in fact, has proven both valuable and essential within the UK among both the welfare of our daily lives and our economy. Although UK arts funding has fallen by 35% over the last decade, the creative industry contributes £10.8 billion to the UK economy. The Creative Industry has also been essential for the well-being of communities during the Covid-19 pandemic by keeping us not just entertained and connected, but encouraging home making and home workshops for families. This has been evident through the success of #isolationartschool, the free Instagram academy founded by artist Keith Tyson who brought together creatives with those who wanted to learn during lockdown. Channel 4 opened an emergency weekly slot for ‘Grayson’s Art Club’ with artist Grayson Perry, aimed at “Making something uplifting in response to the crisis.”

Prior the Covid crisis, the creative industry helped bring people together to enjoy and celebrate festivals and events which engaged us with workshops, performance, film screenings and other various gatherings. These things were on our doorstep in the North West of England, delivered by art organisations like Super Slow Way (Pennine Lancashire), Deco Publique (Morecambe), Prism Contemporary (Blackburn), and In-Situ (Pendle). Art organisations which are becoming engrained into the daily lives and desires of our communities. Having responded to the current climate, these organisations and communities are still engaged through the utilization of virtual platforms and means of communication and engagement.

We are what we say we are.

These communities highlight the imbalance between what we are and what the media say we are. And in the midst of the current climate, now is a more vital time than ever to re-appropriate the perceived narratives around working class people and places. This can (and is being) achieved through the determination of grass-roots community support within the creative and cultural sector of working-class towns like Blackburn. Creatives who aren’t flown into our towns with little understanding of our people and places, but rather are our people and places. Artists, practitioners, and academics collaborating on meaningful projects which our people can relate and respond to. Resisting the threat of internalised oppression and organically re-generating our town and uniting our people through art and culture.

So, for me, the conference is an opportunity to share my work/practice and what I DO as a working-class student and artist in Blackburn. On Tuesday the 14th I will be presenting my paper: Action research: Could we as a community of diverse creatives in Blackburn re-establish the narrative of ‘Creative Placemaking’ within a working class town in which we co-exist? Throughout this I will discuss my action research within socially/community engaged projects, and my critical and artistic responses to them among the re-generating landscape of Blackburn.

We are what we say we are.

The misfortunes of our people and places are sadly apart of our reality. The perception of these people and places conditioned into society by the media are flawed and misleading, part of a perpetual stream of poverty porn. A narrative which is contrary to the real lived experience of many working-class people, academics, and artists. Escapists who although are subject to many disadvantageous situations are driven by a desire for something other.

By coming together at the Working Class Academics Conference and sharing experience and learning, we can become stronger. Together we can challenge the impositions made on us through our own perspectives, our own experiences and achievements. A celebration of what we are doing as both individuals and collectives. Working class communities which should and will be recognised and celebrated for what they are – places where working hard and self-discipline sometimes just isn’t enough; but places where we unite, support and grow. Places of which we are ‘Essential’ to re-generation processes. People and places which manifest both cultural norms and cultural excellence.

We are what we say we are. And we have a lot to say.

Helen Wall

15/07/2020 @ 7:52 am

I so recognise what I have read here. In Barrow we are stigmatised for drugs deaths, Victorian housing, some of the most deprived areas in Europe etc, and yet I have found the town bristling with creative people bursting with talent and skills and appreciation of others’ art and culture.